IPA: What effects might the Charlie Hebdo attack have on freedom of expression, particularly satire? How worried are you?

Zapiro: I’m very, very worried. It was a horrendous attack on so many things; not just on Charlie Hebdo but on the media, on cartoonists, on freedom of expression, on satire and on secular democracy as a whole.

It’s great that we’ve witnessed this tremendous group solidarity as a result of the attack, especially in Europe. But it doesn’t change the fact that there is now more fear among writers, satirists and editors, as they try to figure out how far they can go on certain subject matter.

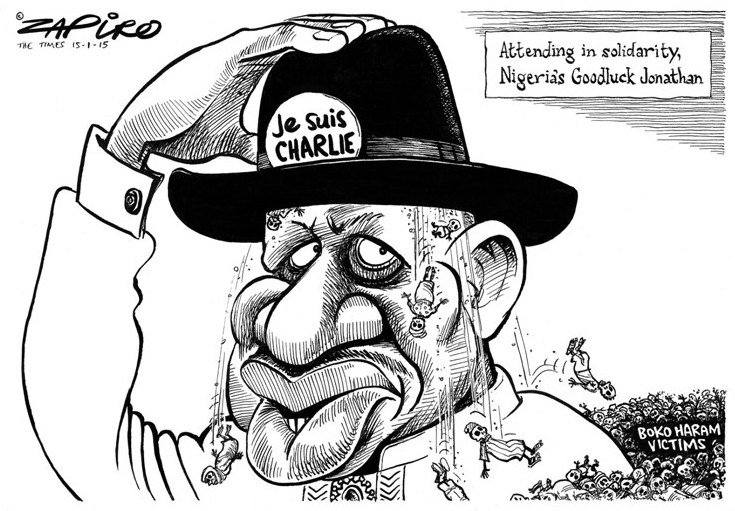

IPA: There seems to be a backlash against Charlie Hebdo and its values in many states, including in Africa.

Zapiro: The hypocrisy is breathtaking. You had African heads of state marching in Paris for freedom of expression, while at the same time censoring media reports at home. Unfortunately populism is rife in many countries, and politicians are playing to all kinds of galleries.

In South Africa, media’s timidity to publish Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons has been very disappointing. I’d hoped that here at least, where we have a fairly free print media, they’d feel able to publish them. Instead I see a lot of caution, a lot of self-censorship and a lot of fear.

It’s a far cry from the euphoria of 1994 when we emerged from the dark years of censorship and repression with a new constitution that guaranteed tremendous freedom for print media. Nelson Mandela once said to me, “it is your job” to be critical of government.

Unfortunately, we’re now seeing a backwards slide and state attempts to shut down freedom of expression. I’ve been on the receiving end of two lawsuits from the President. It’s sad that the governing ANC party, the organization which brought us all these freedoms, is now the problem rather than the solution, but it’s typical of most liberation movements and most dominant political parties. All power corrupts.

Many African countries have dignity laws which prevent their leaders from being denigrated and there are moves in South Africa to adopt something similar. Then you’re on the slippery slope to dictatorship. Luckily, we have a strong civil society which can be mobilized to defend freedom of expression. But we’re in a fight.

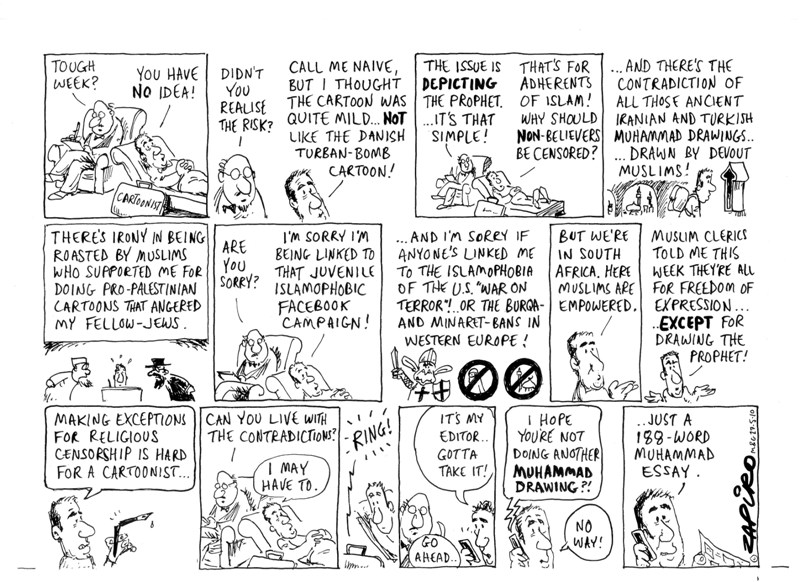

IPA: You mentioned self-censorship. Can you explain how you, personally, decide what to (and what not to) publish? What criteria do you use?

Zapiro: My line is clear. Material that directly and unequivocally incites people to kill or hurt should be banned, although I’ve noticed that this kind of content tends to be produced by political or religious extremists rather than humorists. Taste is so subjective that unless something contains that direct incitement, it should be allowed. I support the right to publish things that could be seen by some people as offensive. I don’t like homophobic, misogynist or racist material, but it shouldn’t be censored.

I check to see whether something works as a concept and whether I can justify it with my principles. I never go out of my way to gratuitously hurt or insult any group, but rather to make certain points. If someone along the way gets offended, that’s not going to stop me.

IPA: What do you hope will be the legacy of the Charlie Hebdo attack?

Zapiro: I hope the massive displays of solidarity will have an energizing effect in getting governments to stand up for freedom of expression. In any state that considers itself free, people must have the right to publish satire, to criticize religions and politicians, and to be irreverent.

I also hope those same societies will reflect on how social exclusion and inequality were root causes of the Charlie Hebdo attack.

As for me, I’ll continue to defend the right to publish.

www.zapiro.com