Children are now skilled users of the internet, smart devices, social media. What does this imply for education, specifically for teachers?

It is true that there is often a gap in the digital competencies of old and new generations. But the exact nature of this gap is often elusive: are children really ‘skilled users’ of the Internet? Not necessarily: most are skilled users of smartphones and mobile devices, but this doesn’t imply the ability to search, evaluate, or produce complex and useful information within digital environments. The set of competences included in the idea of ‘information literacy’ is rich and articulate, and information literacy requires training and critical thinking. I would say that today most kids (not all) are proficient in quick, ‘horizontal’ information surfing (moving from a bunch of information to another), while most of them are not proficient in working with ‘vertical’ complexity: complex, structured information requires analytical tools that must be acquired.

It is true that there is often a gap in the digital competencies of old and new generations. But the exact nature of this gap is often elusive: are children really ‘skilled users’ of the Internet? Not necessarily: most are skilled users of smartphones and mobile devices, but this doesn’t imply the ability to search, evaluate, or produce complex and useful information within digital environments. The set of competences included in the idea of ‘information literacy’ is rich and articulate, and information literacy requires training and critical thinking. I would say that today most kids (not all) are proficient in quick, ‘horizontal’ information surfing (moving from a bunch of information to another), while most of them are not proficient in working with ‘vertical’ complexity: complex, structured information requires analytical tools that must be acquired.

The digital world still needs to move from fragmentation to vertical complexity, and E.M. Forster’s motto “live in fragments no longer!” is perfectly suited for today’s digital landscape: the Internet is still waiting to move from the age of the first urban settlements and exchanges, to the age of (information) cathedrals. This is probably the main task that awaits the new generations, and this is the real challenge for teachers and educators: we should use our new learning technologies and environments, our new digital devices and resources, as complexity-oriented, empowering tools, not just as ‘surfing’ tools. Providing the students with the ability to produce, select, manage, evaluate, disseminate complex digital information should be among our fundamental teaching objectives.

How is storytelling different in the digital age?

Even in the digital age, good and compelling ‘stories’ are basically linear. But the ‘line’ of storytelling is no longer limited to one medium or to one code (be it writing, audio or video): transmedia storytelling is a much more powerful way of telling stories. And the ‘linear’ story doesn’t always need to be told in a fully linear way: among the tasks of the audience might well be that of re-constructing the ‘story’ from partial information given through different media or in different times. However, the authors should know their stories well, and in advance. The activities of story building, of world-building, require careful, consistent planning and design. This is true in narrative, but also in education and learning: learning content should not be considered as a collection of scattered, fragmented, self-sufficient, independent pieces: the good use of learning resources requires planning and design – and requires storytelling!

There is no point in having digital textbooks that are basically PDF versions of printed textbooks: digital textbooks should include multimedia content, data animation, interactive content, simulations… and not as bonus or ‘added materials’, but as key components of their storytelling. This requires careful learning design and good editorial skills: producing effective digital textbooks is a complex task, and requires ‘strong’, not ‘weak’ authorship.

You say learning resources should be multi-layered. Can you explain what you mean?

If we take seriously the idea of ‘narrative’, storytelling-based learning, we should also take seriously – and address – one possible and very reasonable objection: kids and students are different, and often require personalized learning paths and learning resources. How can we offer both ‘strong’, well designed, almost ‘narrative’ content, and the ability to accommodate different learning needs, habits, interests?

Content layers are the best solution to this problem. We often tend to ‘collapse’ optional or integrative learning content within the main ‘story’. This might be due to the influence of mark-up languages which work this way, collapsing integrative content and metadata within the main body of primary information. But this is not a good idea when we are designing learning resources, and particularly digital textbooks. Layers are a much more effective and ‘clean’ solution: the basic narrative is the same, but different users (or the same user in different situations) can add (or ‘activate’) different layers of well-structured, additional information.

Layers can also be used to connect different fields or topics: a ‘bridge’ layer can connect the digital textbooks for physics and philosophy, or for history and literature. Layers can add geo-referencing and chrono-referencing. Layers can be used to handle multi-language content. And so on!

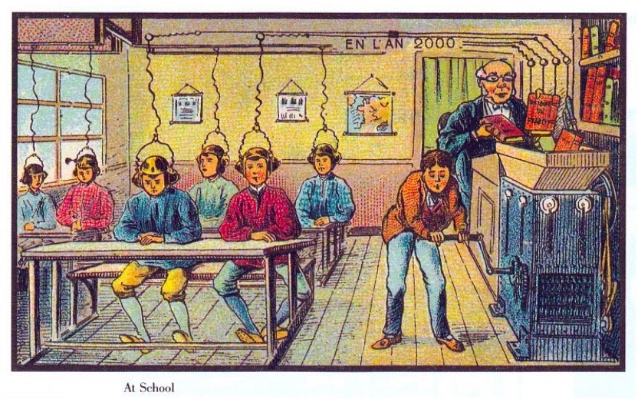

How do you imagine the classroom of 2050? What do you hope will be possible? What do you fear?

2050 is way too far in the future to attempt any reasonable prediction. I would expect a large use of virtual and augmented reality, and I am convinced that data animation and immersive environments will be among the most interesting and promising fields to follow. But real innovations are always difficult to predict: the (far) future is predictably unpredictable.

The fears are much more constant in time: authoritarianism, lack of choices and of critical voices, conformism… all of them might well flourish in digital environments as well as in traditional ones, even if under different names or in different forms.

Will there still be a role for professional educational publishers? If so, what will it be?

Absolutely. The task of producing good digital learning resources and new learning environments is a complex one. Producing a good digital textbook is more difficult, and requires more professional skills, than producing a good printed textbook. Professional educational publishers are not going to disappear. But they will face many challenges: the need for new skills, a deep change in the business models… and professional publishers should learn to coexist and collaborate with producers of open content and with open projects such as Wikipedia: opposing them would be the worst of mistakes.