The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was founded in 1967 in Bangkok as a regional forum with the aim to promote political cooperation and stability, trade and economic expansion, as well as social development in member countries. The founding members were Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Brunei joined the association in 1984, followed by Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999.

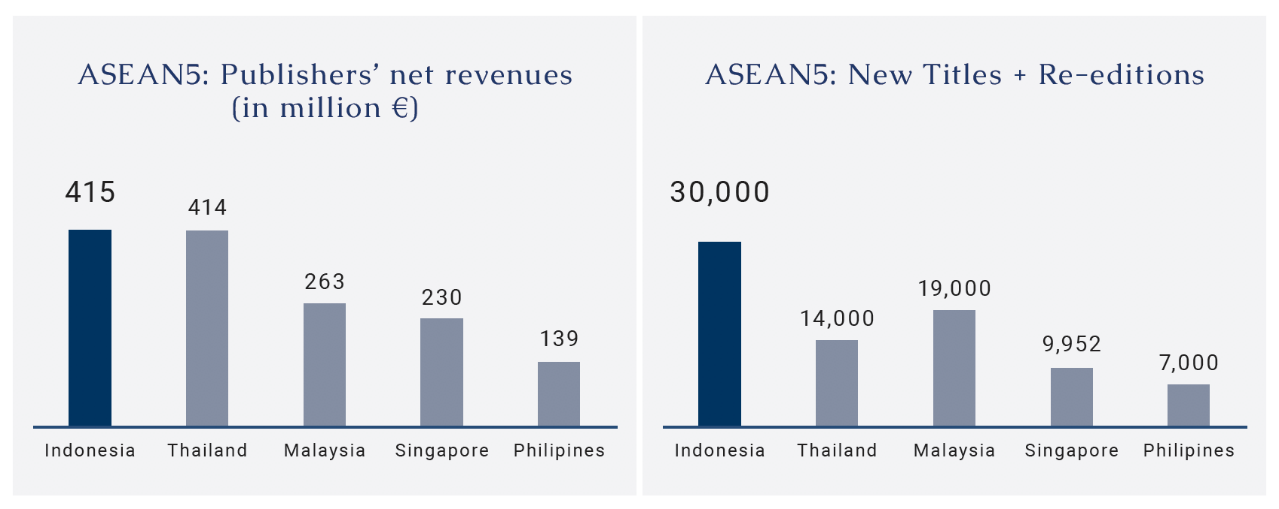

Book publishing in Southeast Asia began in the early twentieth century. The book market in the first five ASEAN countries in 2014 amounted to EUR 1,461 million (USD 1,654 million).

Source: London Book Fair 2019: Indonesia

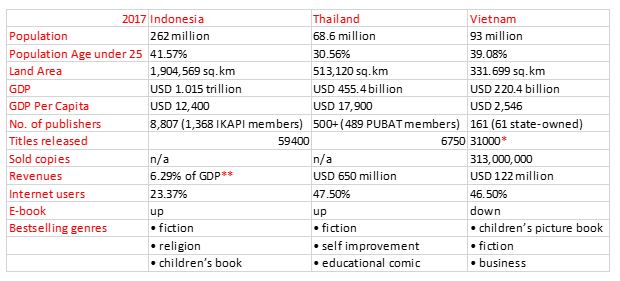

Comparing three ASEAN countries, with three different political systems, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, gives a very interesting picture of the region.

*Including school textbooks

**Including newspapers and magazines—Indonesian Creative Economic Agency,

Sources: World Factbooks, Laura Prinsloo, Indonesian Publishing Industry Report 2019, PUBAT Thai Publishing Industry Report 2017, Personal communication with Tran Phuong Thao, ThaiHaBooks Publishing House and Laura Prinsloo, Indonesian National Book Committee

The market share of educational books to general books in Indonesia and Vietnam is 60:40 percent and 80:20 percent respectively, while in Thailand it is 30:70 percent. Demography-wise, Indonesia and Vietnam have high birth rates with 40 percent of the population under the age of 25; it is certain that the growth of educational books, children’s books, and books for professionals will increase in the coming decade.

Policy

Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s policy to promote the creative economy has led to his government’s support for literary-related initiatives. Indonesia was the Guest of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2015 and the Market Focus country at the London Book Fair in 2019. These two international events required enormous human and financial resources, let alone vision. Indonesia plans to set National Book Committee to be an independent agency to continue its work to promote reading culture at home and Indonesian literature abroad. Indonesia’s government also set a budget for textbook procurement through the Ministry of Education and Culture. The present administration also allocated 2% from its provincial budget for village libraries.

Besides 200 percent income tax exemption if a business donates books and educational equipment to a government-listed educational institution, Thailand has never had a policy concerning the publishing industry. The Thai Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Culture have only focused on reading promotion. School textbooks are provided to pupils free-of-charge, with an annual budget of USD 190 million.

Similar to Thailand, Vietnam’s government focuses on reading promotion. Private publishing companies were only allowed in 2004, the year Vietnam joined the Berne Convention. Though they are doing well, state-owned publishing companies still monopolize textbooks, and thus the price is low.

Copyright

In Thailand, 2018 was a sensational year for one historical romance set in the seventeenth century, Bupphesaniwat (Love Destiny) by Romphaeng (pseudonym). The book was released in 2010. It took the scriptwriter a few years before the production for television was made, and the first episode was broadcast on February 11, 2018, and the last episode, the fifteenth, aired on April 11. In two months’ time the book sold over a hundred thousand copies. The television ratings went up. Everyone was humming the theme music from the series. Tourism at the old capital, Ayutthaya, where the story is set, boomed. Period costume rental businesses also benefited. The television series, the book rights, and games, were licensed to a publisher in China for a seven figure sum.

It is normal that once a book is made into a television drama, the sales go up. The stock of 5,000 copies was gone within two days of the first episode airing, and the orders from bookstores were pouring in. The reprinting process would take ten days to two weeks—not considering the distribution time requirements. Customers could not wait. Booksellers and readers were threatening the publisher. Many ordered the e-book. However, some decided to scan the entire book and upload it on the Internet, where it was downloaded 70,000 times. To make a long story short, the publisher complained to the Economic Crime Suppression Police and demanded a compensation of 40 million baht (USD 1.25 million). To file the case, the publisher had to print all pages of the book on the website, download the file, or make a sting operation in order to provide evidence. She didn’t succeed.

The irony of this case was that since the series was so famous, her legal attempt was reported on the television channel that broadcast the series. After reporting, the anchor suggested, “Anyone who downloaded the file or shared the link should delete it immediately.” So the evidence disappeared! This was not the publishers’ first case, but she also failed to get compensation for other earlier cases. There were a few publishers who were able to get compensation that was mediated by the police and settled outside of court.

Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam are all members of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS. Hard copy piracy is still practised widely in educational institutions at all levels. College textbooks and reference books are often photocopied in their entirety and bound, while novels and comics are scanned and uploaded to the Internet. Recordings of children’s books, showing every page along with the audible text, are uploaded on YouTube. For K-12, teachers are the ones who photocopy. Though government spending on education is high, in Thailand’s case, 80 percent goes to salaries. The interpretation of “fair use”, limited library budgets, lack of availability and distribution of books are also an excuse (and justification) for piracy.

Two issues that discourage publishers are:

- Public ignorance of the importance of respecting copyright, and a lack of understanding about how the violation of copyright has negative impact on creative economy;

- Enforcement—handled by police—is time-consuming, costly, and often unsuccessful.

As mentioned above, bound photocopied volumes for commercial distribution, and loose handouts for use in schools and colleges are out of control in all three countries. Indonesia and Vietnam have set up an RRO (reproduction rights organization) for some years now; Thailand only has a CMO for music but not publishing and images. With the lack of legal backup and legal licensing, RROs in Indonesia and Vietnam can do very little. In Thailand, one objection was that the higher education institutions would have to pay foreign publishers, but they forget that the K-12 schools are also violating the rights of local publishers.

The Marrakesh Treaty. The Thailand Copyright Act, which recently took effect, raised concern among the international publishing community. The new exceptions it contains had been justified as required for Thailand to implement the Marrakesh Treaty, to which Thailand acceded in January 2019. Despite the efforts of several national and international organizations representing rightsholders, the Thai Copyright Act has been amended to include an overly broad exception benefiting persons with any disabilities (not only the visually impaired) and affecting the rights of reproduction, adaptation and communication to the public.

To prevent the abuse of section 32/4 of the Thai legislation, which goes beyond the scope of the Marrakesh Treaty, the Department of Intellectual Property (DIP) just released the regulation titled “Copyright infringement exception for benefit of people with disabilities that cannot access to copyrighted work B.E. 2562 (2019)”. Some of the details are:

- Seven national entities are allowed to reproduce, adapt, and distribute copyrighted work;

- The reproduction of the works, in the format or platform for the disabilities and distribution to public, must comply with the Berne Convention’s three-step test;

- Each authorized and recognized national entity must notify the DIP about the reproduction or adaptation of the copyrighted work.

Conclusion

The publishing market of the three ASEAN countries considered here has high potential. For Indonesia and Vietnam, with the 40% of population under the age of 25, the growth in the creative economy is certain, with the government policy that strengthens copyright protection systems. Exceptions and limitations have obstructed creative industries’ transition to the digital economy and their development of local quality content, in particular for education. ASEAN governments must provide an appropriate enforcement mechanism to enable publishers to invest in producing books, e-books, and digital formats, by ensuring that investment can be protected through licensing and enforcement if required. Setting up RROs in ASEAN countries would help in promoting the literature and culture within the region. To enable publishers to invest in publishing local authors or translating foreign works into national languages, which ultimately affects cultural diversity, such incentives are necessary.